There’s a surreal feeling before you request a stack of old newspapers at a library, marked by a mix of anticipation, excitement, and the hope that the article you’re looking for lies within. More often, all that you get is decades-old dust released from opening a bound file untouched for fifty years, along with the dread that the fragile newspaper pages might crumble in your hands.

In 2019, as my colleague Tooba Masood Khan and I embarked on our idea of let’s find out what happened in the Mustafa Zaidi case, our sense of curiosity became more of a hacking cough and overwhelming fear that we would never be able to access any official record. After four years, visits to more than a dozen archives and libraries, and the generosity of countless people who opened their libraries, troves of documents, and homes, I can, at least, say that all the dust was worth it.

We now have a book to show for the damage to our lungs and eyes: Society Girl — A Tale of Sex, Lies, and Scandal, a true crime book that looks at the death of the poet and former civil servant Mustafa Zaidi, set against the backdrop of high society and the pivotal changes in Pakistan in 1970-71. By the time we were in the depths of our research, almost every librarian in Karachi knew that we were investigating Mustafa Zaidi’s death, sometimes one of us would meet someone and explain our work and they’d say yes, another girl came by and was asking too. We knew for sure they meant one of us.

So how does one do archival research? As of writing, the National Archives of Pakistan’s page returns a warning on my browser; history itself is too dangerous to look up online, which would be ironic but seems on-brand for Pakistan. The idea of obtaining a historic, verifiable record, of being able to double- and triple-source your work — seems like an anomaly. Much of “newspaper archives” that exist in the public domain — or are easily accessible — are scans of newspaper and magazine pages, often with no dates or sources attached, on Facebook and Instagram accounts dedicated to archival history or on journalists’ and archivists’ accounts.

As there is no context, you can present any version of Pakistani history, depending on your and your audience’s leanings by selecting the right set of archives. The reliance on social media platforms to “maintain” archives means that, of course, they are virtually unsearchable. So, if you’re “looking” for a record, there’s no way you can find it there. While there’s no central repository of these archives, in no way should one assume that a social media account is a lasting and permanent record; we are all one tech bro’s whim away from losing history.

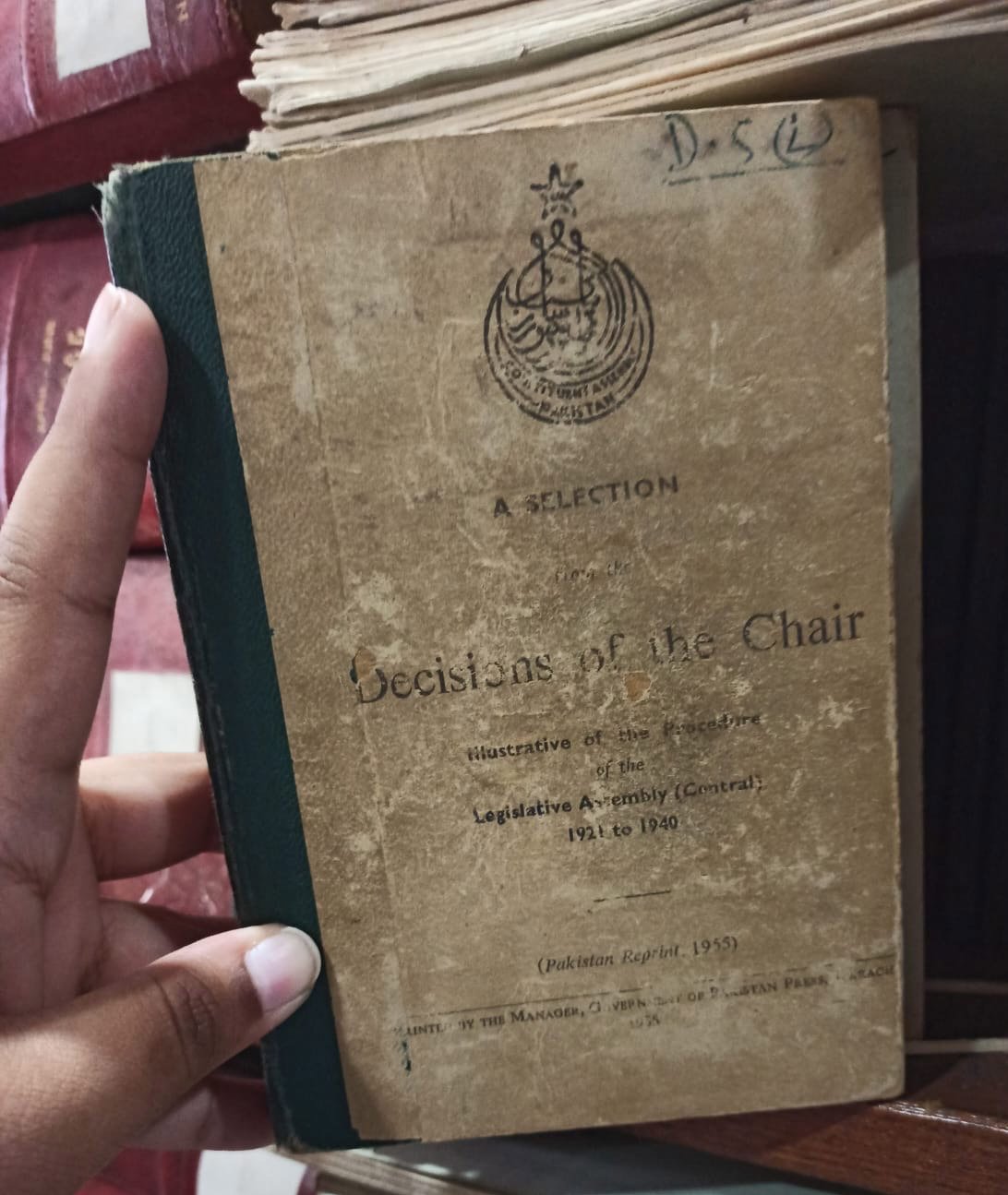

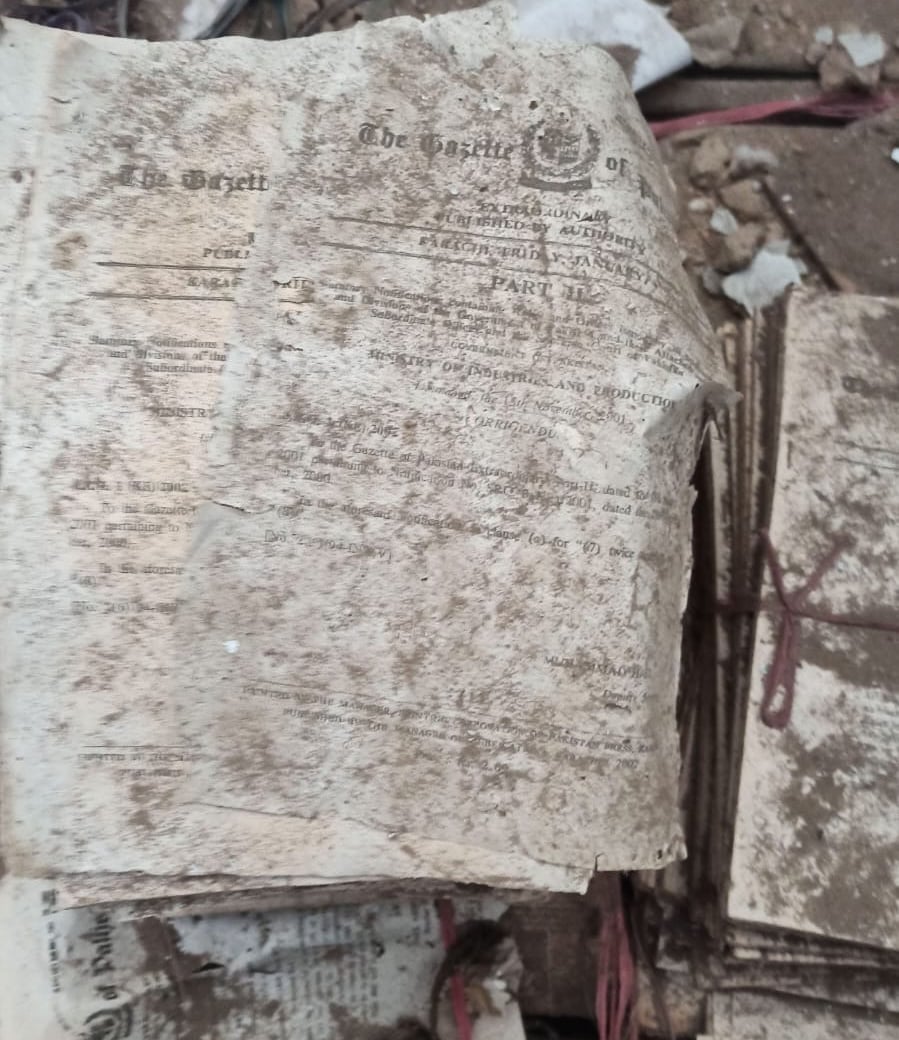

The sad reality is that a considerable amount of Pakistan’s history is archived and digitised — but in university libraries abroad, to which the lay Pakistani researcher has no access. Libraries in Pakistan are few and far between, and when you do find one, it often lacks a catalogue, digitised material, and sufficient staff. The fact that the records of soldiers who had served in the First World War were lying inside the Lahore Museum for over 90 years until they were discovered and digitised is the stuff of movies. Visit the Frere Hall book market on a weekend and one will find historic newspapers and magazines being sold for virtually nothing. But, at least inside what remains of Pakistan’s public and private libraries, a wealth of Pakistani history exists, even if it can sometimes feel (and be) largely inaccessible.

After four years of ‘yeh to nahin hosakta (This cannot be done)’ and ‘kaunse saal ka akhbar? 1970?! (Which year’s newspaper? 1970?!)’ to a point where we were able to collect and digitise hundreds of newspaper pages, one can say this much: Pakistan’s history survives in bits and pieces, through the work of librarians, and of people who are generous beyond belief with their archives. Some of the most fantastic records came to us from people who we had virtually no connection to, who offered their hard-earned archives because they wanted to see them utilised.

We worked in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad for this book, and so the accounts here are largely from libraries and archives in these cities. That said, I have seen Peshawar’s great archive and long to work there and have heard raves about Bahawalpur.

Our starting point for research was initially Dawn, the Pakistani English-language newspaper that was launched in British India by Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah in 1941, where we were able to access their digitised and print newspapers, with the assistance of their staff. Being able to access digitised records saved us hours of having to look through newspaper files, but also meant that the archives didn’t need to be handled again and exposed to the elements, and it was also easy to clip and just save the articles we needed.

As of date, I am unaware if any other media organisation in Pakistan — legacy, or otherwise — has digitised archives or even utilises these in its reporting. (I’ve worked for two media groups and have never been offered or given access to the archives, and once was not even allowed to enter an Urdu newspaper’s building to ask for access.) But as my co-author and I are journalists, it is easier for us to navigate newspaper offices. I cannot imagine what university students must face when trying to access the archives of a media organisation.

Karachi’s Liaquat National Library — which should be a vital resource — is simply put, understaffed and unable to handle the most basic of requests. Newspaper files are piled up in a storage area to which people have no access, you cannot photocopy or scan newspaper pages on the premises, and the state of the files ranged from surprisingly intact to surprisingly dusty. If you’d like “newspapers from 1970” — which was often our starting request — you may only get a few months. Imagine reading a book that starts in January but then you miss out on February and March. It is also impossible to know what newspapers are in stock — through trial and error, the staff’s assistance and persistently asking, is how we managed to access a sizeable number of newspapers there.

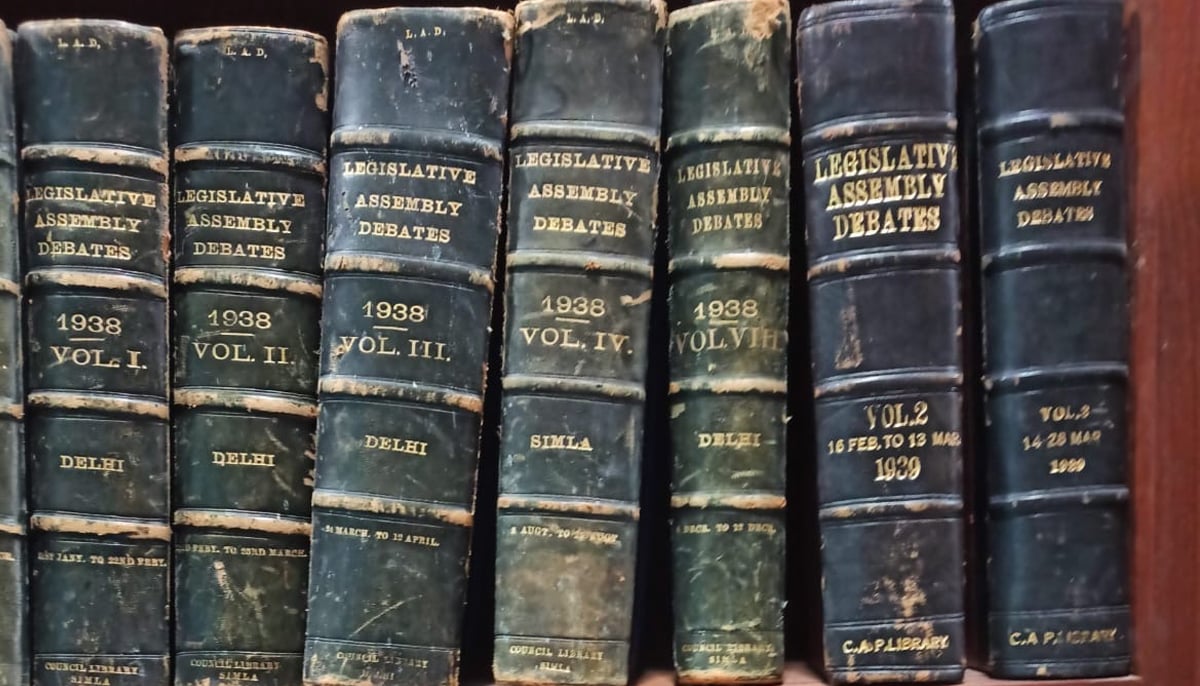

One day in Lahore, we shunted ourselves from library to library, inevitably finding our way to the Punjab Public Library, astounded that we had never heard of the place. It is a fantastic institution where the staff is helpful and professional, and the archives are well-maintained. It has an excellent scanning facility, which means that archives are handled by the staff and properly scanned or copied. It’s a researcher’s dream come true, especially if your focus is on newspaper archives after Partition, and government documents, particularly gazettes. The sad reality is that government files were meticulously maintained at some point; I fear for anyone who is attempting to track down a document produced in the past 20 years. Ironically, it was easier to access, even online, pre-Partition Government of India documents than it was to obtain something from a court of law in Pakistan or from post-1947 police records, which seem virtually nonexistent.

We dug through archives everywhere — like the Punjab Archives, where the surreal experience of sifting through old colonial documents in search of a single name while surrounded by centuries of history was unforgettable. Anarkali’s tomb, one of the most fascinating research spaces, is part of this archive but is limited to pre-Partition documents. We worked at the Sindh Archives, where the staff was helpful but they did not have a categorised list of available newspapers. Similarly, while the National Archives of Pakistan staff is helpful, there is no access to the resources, and one has to specifically request newspapers instead of being able to browse through them, but as my co-author Tooba found, the archives were well maintained and kept in a temperature controlled environment.

But beyond newspaper records, one runs up against a wall. The state of court records is abysmal. At the lower courts in Karachi, it is almost impossible to request a record, and again, record rooms are not open to the public. Asking the high court was just as frustrating, and letters to the registrar went unanswered. There is a store at the high court; again, not open to the public, and — based on anecdotal accounts — in disarray. I almost keeled over in shock when a staffer at the Supreme Court of Pakistan’s Karachi registry informed us that we were not entitled to get access to a case file — and that even if we were a party to the case, we wouldn’t be able to get it.

It is at private libraries like the gem that is Bedil Library in Karachi where we were able to do some of our most substantial, organised research. It is no wonder that PhD students are often in Bedil, researching, or bringing mithai to thank Bedil for their help in completing their work. The library is organised, and immaculately maintained, and Zubair sahib, who runs it, is essential — he gave us advice, made connections, offered phone numbers, provided books, and went out of his way to make sure we had all possible resources. If there was a new source that had been digitised, he would get it to us. In no way would it have been even half as possible to do any work had it not been for their world. Working with someone who not only understands what you’re trying to do but also supports it, and can help provide resources is most of the battle.

In our experience, some practical advice to begin archiving is to have a clear idea of months, years, and even dates if possible; or to try out a few sources — often, we’d ask for Jang, and then work our way through other newspapers. After your first visit to an archive, you’ll get a sense of “where” your material lies and how to navigate it.

Do not get distracted: The urge to read through an entire newspaper from cover to cover is immense. Unfortunately, the library will not be open 24/7, and it’s possible the files will be moved back overnight, and you’ll have to cajole a librarian into finding the files for you again.

Remember to skim through the article to check for continuations and related articles. I had to go back to find continuations because I’d missed that the article continued on another page.

Take phones and battery packs: I used a scanning app, but on an iPhone, there’s now automatic OCR which makes it easier to look up archives later. Other than the Punjab Public Library, we had to scan documents ourselves — and prayed that our phone batteries didn’t run out mid-file.

Listen to the staff: This is hard work and the assistants have to lug files back and forth.

Be generous with other people: Gatekeeping has led us nowhere. The researcher Rohail Salman had helpfully posted a list of all the documents he had collected during his research on Twitter and provided access to people who inquired; the writer Sanam Maher reached out to us when she found something related to our research.

For every helpful person, there were far more who would tell us that they didn’t really have much. They would promise to show photographs and then flake out, or simply wouldn’t want to share. Much of that record will die with them; perhaps they’re hoping to line their graves with old newspapers and photos. Sometimes I wonder if they’re actually gatekeeping this knowledge, or if they simply think it has no value — entirely depressing prospects.

So, here’s a plea: please consider donating or digitising your family’s archives before throwing them out. Those stacks of newspapers, old magazines, diaries — they all have value. They could make or break someone’s research. What will you do with your great grandfather’s papers, in a country so threatened by climate change where just one bad evening of rain could flood an entire library and consign Pakistan’s much-contested history to mush? The desire to gatekeep a family’s archive — particularly if you are from a notable family that has played any role in Pakistani politics, society, or its economy — is nothing to be proud of. You might as well unleash whatever imaginary skeletons you think are hiding there — Pakistan deserves more truth if nothing else.