In the 2018 general elections, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), led by former cricketer Imran Khan, stormed to a majority, surprising analysts and unsettling the country’s established political parties.

Making history, a ruling party was voted back into power for a second consecutive term and with an even stronger mandate — a first in the province’s political history.

The party came back stronger — from a simple to a two-thirds majority — in the Provincial Assembly. So, the message was clear: the party is here to stay.

Following the general elections on February 8, 2024, PTI hit a political hat-trick, emerging as the dominant force in the province, yet again. As things stand today, the party remains as politically potent as it was in previous elections.

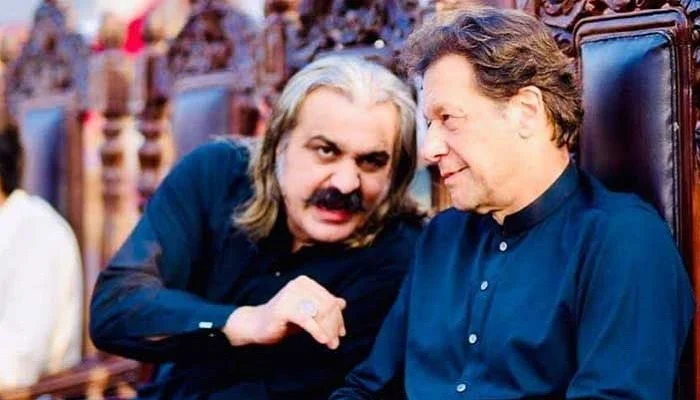

That said, PTI has long struggled with internal organisational rifts that remain unresolved. Since Imran’s ouster from the PM office on April 22, 2022, the KP chapter of the party has maintained a posture of resistance — a stance now set to be tested once more. With the PTI founder closing the door on negotiations, he has announced a protest movement starting August 5. This time, in a first, his two sons will also join the campaign on the frontlines — signalling a shift in both strategy and symbolism — to support their father, who is currently serving time in Rawalpindi’s Adiala jail.

KP’s politics has been reshaped over the last three to four decades, largely due to the impact of two Afghan wars that pulled the province into prolonged instability and conflict. KP politics has reshaped over the last three or four decades, particularly due to two Afghan wars, which plunged the province into chaos. Thus, from the ‘red-shirt’ dominance in KP politics for many years to the ‘green-shirt’ change led by Imran. Where it will now lead — to more chaos or stability — remains to be seen.

Unlike many other politicians, Imran was no stranger when he entered politics for the first time in 1996. Already a front-page story as the cricketer who led Pakistan in the 1992 World Cup, Imran’s position on the ‘War on Terror’ and his stance against military operations in the former FATA made him stronger, as did his resilience and resistance. However, he has often been criticised by his opponents — then and now — for having close links with the banned outfit and even dubbed as ‘Taliban Khan’ by some. In the 2013 elections, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) launched a murderous campaign against secular parties, killing many leaders.

The issue came into sharp focus during the 2013 general elections when the banned TTP openly attacked the Awami National Party (ANP) and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), taking out many leaders and political workers.

These assassinations changed the province’s political landscape forever.

Imran’s one-man army turned the tables in a province that was historically dominated by parties like the erstwhile National Awami Party (NAP) or Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI).

The failure of two coalition governments — Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) from 2002 to 2008, and the PPP-ANP alliance from 2008 to 2013 — opened space for change. It was the third coalition government of PTI and JI, from 2013 to 2018, which gave a real boost to Imran and PTI, enabling it to sweep polls in 2018 and repeat the feat in 2024.

Thus, the fall of both left- and right-wing parties and their alliance gave space to Imran. However, it was not merely Imran’s stance against the military operation in Waziristan that helped him. In 2013, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) targeted and killed opponents of Imran, especially from the ANP, limiting their ability to campaign and indirectly benefiting him.

The province, once known for Bacha Khan’s political philosophy of non-violence, had turned most violent in the 80s with the rise of the Afghan Mujahideen, who launched Jihad-e-Afghanistan against the Soviets. This was followed by 9/11, and the same Mujahideen, when they turned against the US, were branded as terrorists. All this made KP the worst-affected province, resulting in massive killings, drone attacks, and suicide bombings.

As with the philosophy of Bacha Khan, KP politics is also divided into nationalists and religious parties, resulting in back-to-back failures of political and non-political forces.

Veteran bureaucrat Roedad Khan, who died a few years back, told me an interesting story about how he was assigned a job to crack down on Bacha Khan, or Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s Surkh Posh Tehreek, as part of his first assignment after being selected in the first batch of the Pakistan Civil Service, which replaced the Indian Civil Service in 1949.

“Mazhar, you would be surprised that among my first assignments was to crush Ghaffar Khan’s movement and also to keep a check on left-leaning journalists in KP,” he revealed.

“I did my job well,” he confessed.

The NAP eventually emerged after the state banned the Communist Party of Pakistan, crushed Bacha Khan’s “red-shirt” movement, and cracked down on progressive parties from East Pakistan to West Pakistan. Established in 1957, NAP’s founding members included Pashtoon leaders like Bacha Khan and Abdus Samad Achakzai, and Baloch leaders like Mir Ghous Bux Bizenjo and Sardar Attaullah Mengal. Sindhi nationalist GM Syed, Mian Iftikharuddin — both formerly part of the Muslim League — and Bengali leader Maulana Bhashani were also among its key founders.

Many believe that had elections been held in October 1958 as planned, NAP would have won, just like it did in East Pakistan in 1954.

Khan was also of the view that one of the main reasons behind the imposition of martial law in October 1958 by president Sikandar Mirza, a retired major general who was soon replaced by the army chief and then defence minister Ayub Khan, was the likely success of NAP.

“Yes, the state was scared of the rising popularity of the left, which they thought was completely at odds with what the Muslim League had aimed for,” Khan, who himself remained close to the establishment throughout his bureaucratic career, stated.

Despite all state repression, the NAP almost dominated politics in East Pakistan and most parts of West Pakistan, except Punjab. Martial Law was imposed to keep a strict check on the growing popularity of leftist and progressive groups, including the National Students Federation (NSF). The right-wing, which was part of the Muslim League at the time, split after the West Pakistan chapter of the party went against the East Pakistan group led by Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy.

When Ayub resigned, he gave power to General Yahya Khan. This was after a strong movement against Ayub, led by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. Bhutto became popular quickly because he understood politics well and was a strong speaker, even though his role in Ayub’s government drew criticism. He wasn’t seen as a leftist or rightist, but his hard stance against India made people see him as a nationalist. After the China-Soviet political split — which also affected NAP and NSF — Bhutto leaned towards China. His progressive agenda and the slogan of roti, kapra aur makan (food, clothes, and shelter) also drew support away from right-wing parties. He formed his party in 1967 and, within three years, swept Punjab and Sindh in the 1970 elections.

The state’s overall policies towards East Pakistan led to a situation that gave a major boost to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who had once supported the Muslim League and even worked as a polling agent for Mohtarma Fatima Jinnah. Still, NAP did not perform badly and managed to form coalition governments in KP and Balochistan.

Bhutto’s two biggest political blunders, which ultimately gave space to the right-wing and religious parties, were his role after the 1970 elections and, later, when he dissolved the Balochistan government of the NAP. In protest, JUI chief Minister Maulana Mufti Mahmood, father of Maulana Fazlur Rehman, also dissolved the then-NWFP government. Bhutto fell into the trap of the right-wing, which eventually joined hands with General Zia-ul-Haq, who had superseded seven generals and later imposed Martial Law on July 5, 1977. Unfortunately, some NAP leaders, reacting to Bhutto’s repressive politics and the operation in Balochistan, also sided with Zia. This marked the beginning of the end for NAP and left-wing politics in Pakistan.

KP and Balochistan politics were completely reshaped during General Zia’s rule and in the post-Zia era. Pashtoon, Baloch, and Sindhi nationalists, after the fall of the NAP, could not revive the old party. Their narrow political approach confined them to limited nationalist politics, which suited the state. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan turned out to be a disaster not only for Pakistan — especially KP and Balochistan — but also for left-wing politics.

The situation on the western border is still tense, and Pakistan’s relationship with Taliban-led Afghanistan is one of ‘love and hate’. Any serious move to oust the Chief Minister Ali Amin Gandapur-led PTI government could lead to further chaos.

But as the PTI founder has now doubled down on his aggressive politics, the situation could go from bad to worse. The options for the centre are limited, as imposing the Governor’s Rule after the 18th Amendment is not easy. Any such move could be a disaster — but then, our politics is full of both adventure and disaster.

Politically, Manzoor Pashteen, leader of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM), poses a far bigger challenge to PTI and Imran than the PPP, ANP, or JUI-F. So, interesting times lie ahead — as they say, there is never a dull moment in Pakistan.